Willie Ruff retires having given “conservatory without walls” a home at Yale

Willie Ruff was born in 1931 in Sheffield, Alabama, a rural town on the south side of the Tennessee River. As a child, he showed an aptitude for music and immersed himself in the musical resources of his community. A neighborhood boy shared his drum set with young Willie and they became lifelong friends. The pianist at church became his piano teacher. But the best music he heard was the drumming in the African Pentecostal church half a block from his house. “We would sit on the ground outside the church and listen to the people playing those drums,” Ruff recalled. “It was the most exciting, the most moving music. I heard them in my sleep.”

Across the river from Sheffield stands Florence, the hometown of W.C. Handy, the “Father of the Blues.” Handy visited Ruff ’s elementary school classroom, played for the children, and accompanied their singing. “W.C. Handy was a big presence in my world,” Ruff recounted. “When I saw him on stage in my school, talking about the importance of our musical heritage, I said, ‘I want to do that.’ I think I have.”

At 14, Ruff joined the U.S. Army. He was assigned to the 25th Infantry, an old and distinguished African American unit formed just after the Civil War. The Army turned out to be an excellent place to train as a musician. He learned to play the horn and met pianist Dwike Mitchell, who taught Ruff to play the bass and later became his longtime musical collaborator. The Mitchell-Ruff Duo traveled the country and the world for nearly 60 years, famously performing in the Soviet Union in 1959 and in China in 1981.

While stationed at Lockbourne Air Force Base in Ohio alongside the Tuskegee Airmen, Ruff happened to read an interview with the famous jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker. Parker was quoted as saying he would like to go to Yale and study music with Paul Hindemith. “I figured if Yale was good enough for Charlie Parker, it was good enough for me,” Ruff said, laughing.

He applied, was accepted, and enrolled under the G.I. Bill at YSM, where at the time students earned undergraduate and graduate degrees. He completed his bachelor of music degree in 1953 and his master of music degree in 1954. Hindemith, a German composer, music historian, and conductor, was Ruff ’s teacher and an enormous influence. Ruff said he learned “everything” from Hindemith, citing one course in particular: The History of the Theory of Music. “It was my first serious foray into early music,” Ruff explained. “We started at the beginning of polyphonic music and went from there.”

While Ruff was a student, Hindemith worked steadily on an opera about the 16th century astronomer-mathematician Johannes Kepler and the ancient theory of “music of the spheres.” Similarly following an interdisciplinary path, Ruff has forged creative connections between music and other elds, collaborating for many years with faculty across the University including those with expertise in astronomy, geology, computer science, and medicine. He recently traveled to Linz, Austria, to attend a performance of Hindemith’s Die Harmonie der Welt (The Harmony of the World, composed in 1957). It was his first experience hearing a Hindemith opera in person.

Ruff joined the YSM faculty in 1971 at a time of national turmoil and violence. Yale, he recalled, was recovering from the May Day 1970 protests sparked by the New Haven trial of members of the Black Panther Party. “It was a propitious time for me to broach an idea I had with Kingman Brewster, then president of the University,” he said. Ruff proposed that the University invite Duke Ellington, whom Yale had recently awarded an honorary doctorate, to return for a special event to honor him and other luminaries of African American music. “Brewster said, ‘That sounds like a great idea, but we don’t have the money,’” Ruff recalled.

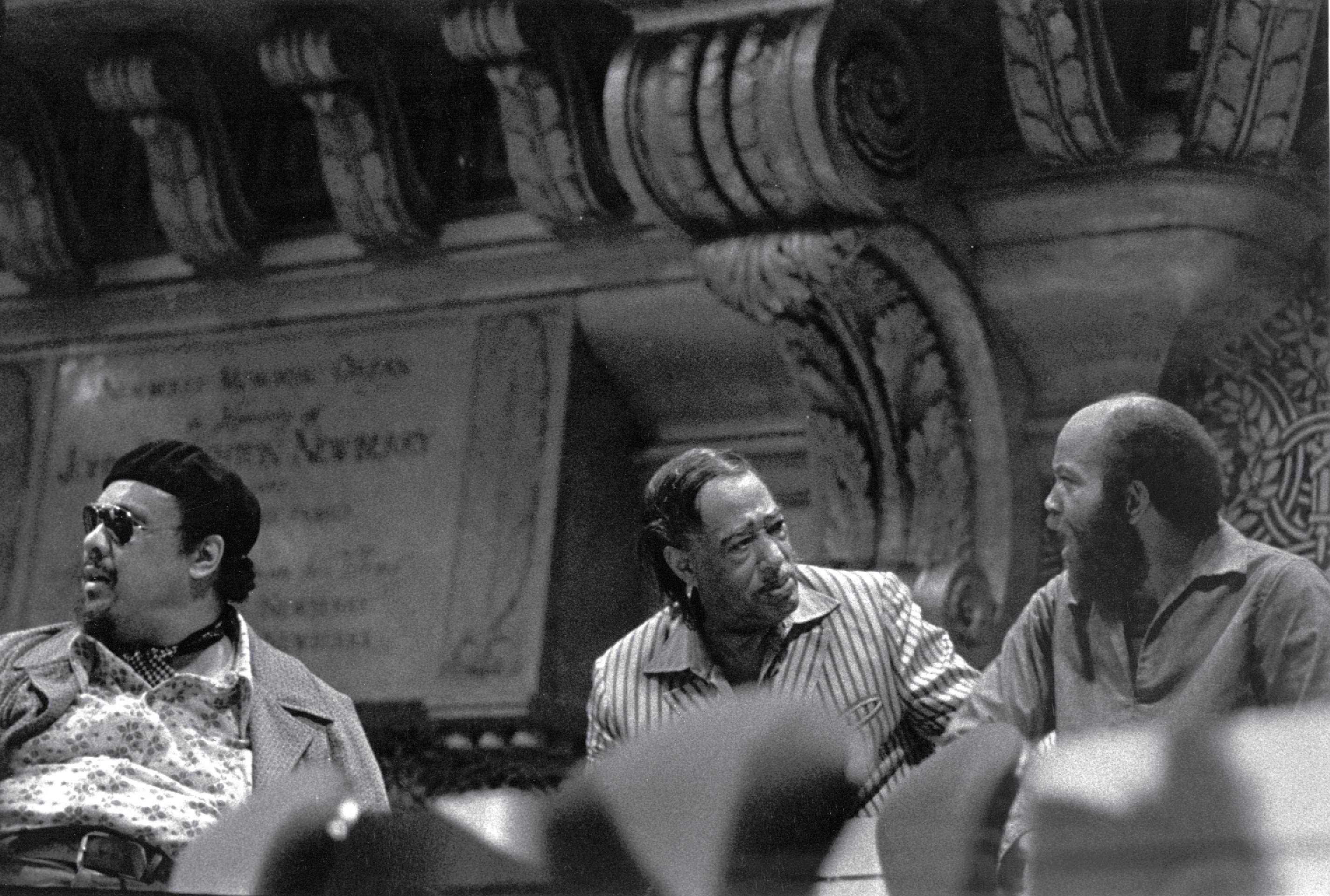

Within a year, Ruff had raised the money, and in 1972 he organized a concert at Woolsey Hall that featured 40 of the greatest musicians of our time, performers like Ellington, Paul Robeson, Marian Anderson, Dizzy Gillespie, Charles Mingus, Roland Hayes, William Warfield — the list goes on. The University honored them with inaugural Duke Ellington Medals and the Duke Ellington Fellowship was born.

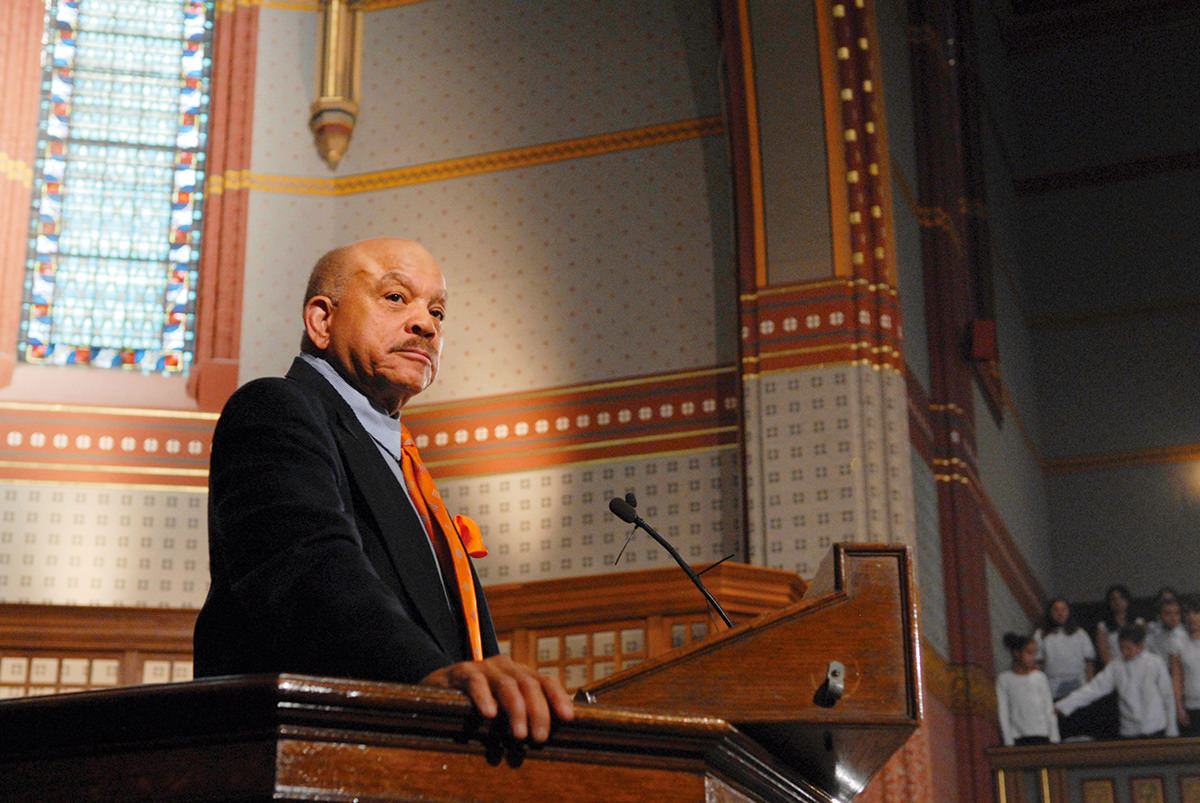

“The idea was not to have these people come, flex the muscle of genius, and then go home,” Ruff explained. “The idea was to establish a relationship.” Since then, under the auspices of the Ellington Fellowship, more than 150,000 New Haven schoolchildren have heard the greats of jazz “live” and participated in workshops with them, either on the Yale campus or in the public schools. Today, this program, Ruff’s singular gift to Yale and the New Haven community, continues to celebrate what Ruff calls the “conservatory without walls” — the “invisible institution” through which African American music has been nurtured and developed over time.

One of Ruff ’s most important contributions to musical scholarship was his discovery of present-day line singing, church music in which psalms are sung responsively between a solo voice and the congregation. Line singing is not notated and exists only in the oral tradition. “I thought it had died out,” he explained. “I accidentally discovered it in a small black Presbyterian church in North Alabama.” Ruff eventually traced the music to a diverse group of churches in the United States, including black, white, and Native American churches, and to Scotland. In 2005 and 2007, he organized international conferences on line singing, both at Yale. His discoveries are the subject of a documentary film, A Conjoining of Ancient Song, and have been featured on National Public Radio.

The prodigiously talented Ruff is also a master storyteller who generously shares his life with others in conversation. In 1991 he published A Call to Assembly: The Autobiography of a Musical Storyteller, a critically acclaimed memoir for which he won an ASCAP Deems Taylor Award for Music Writing. When Ruff tells stories, his Southern heritage shines through. A great oral historian with an epic sense of time, he connects with his listener as if sitting on a front porch in summer, intertwining personal narrative, sensory experience, and historical context.

In his final semester at YSM, Ruff taught one of his most popular courses, Instrumental Arranging — what he calls a “history of the theory of music under the umbrella of arranging” — as well as Edison’s Talking Machine and the American Jazz Century. In the latter course, he’s drawn heavily on interviews he recorded in 1974 with numerous jazz greats including Gillespie, Ethel Waters, Eubie Blake, Earl Hines, Benny Carter, Miles Davis, and others. He recently donated his original set of these recordings to Yale’s Oral History of American Music project (OHAM).

Upon retirement, Ruff plans to return to his roots. He’ll reside in the small town of Killen, Alabama, not far from Sheffield and Florence, in the beautiful home and studio he’s built there. His farewell to New Haven will be bittersweet. He said he won’t miss the New England winters, but he will miss the School and the people who have meant so much to him for so long.

It’s difficult to imagine YSM without him, but, fortunately, Ruff plans to continue sharing his remarkable gifts and stories with others as he works, travels, and lectures. “I’m going to visit the institutions of the world,” he said. “I’m warming up the show and taking it on the road.”