Charles Mingus’ jazz-orchestra epic, "Epitaph," celebrates composer’s genius

On April 2, the Ellington Jazz Series, led by Artistic Director Thomas C. Duffy, will present a rare performance of Mingus’ jazz-orchestra epic, Epitaph. Scored for double big band, Mingus’ magnum opus defies categorization while reflecting the composer’s extraordinary artistic vision and offering the world an experience of the man himself and the ideas that animated him.

Mingus established himself as a virtuoso bassist in the 1940s and 1950s, working with the likes of Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, and Charlie Parker, and further distinguished himself as a fearlessly idiosyncratic composer throughout his career and until his death in 1979. Gunther Schuller, who conducted the only complete performances of Epitaph—at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in 1989 and in New York, Chicago, Cleveland, and Los Angeles in 2007—described the work as “among the most important, prophetic, creative statements in the history of Jazz."

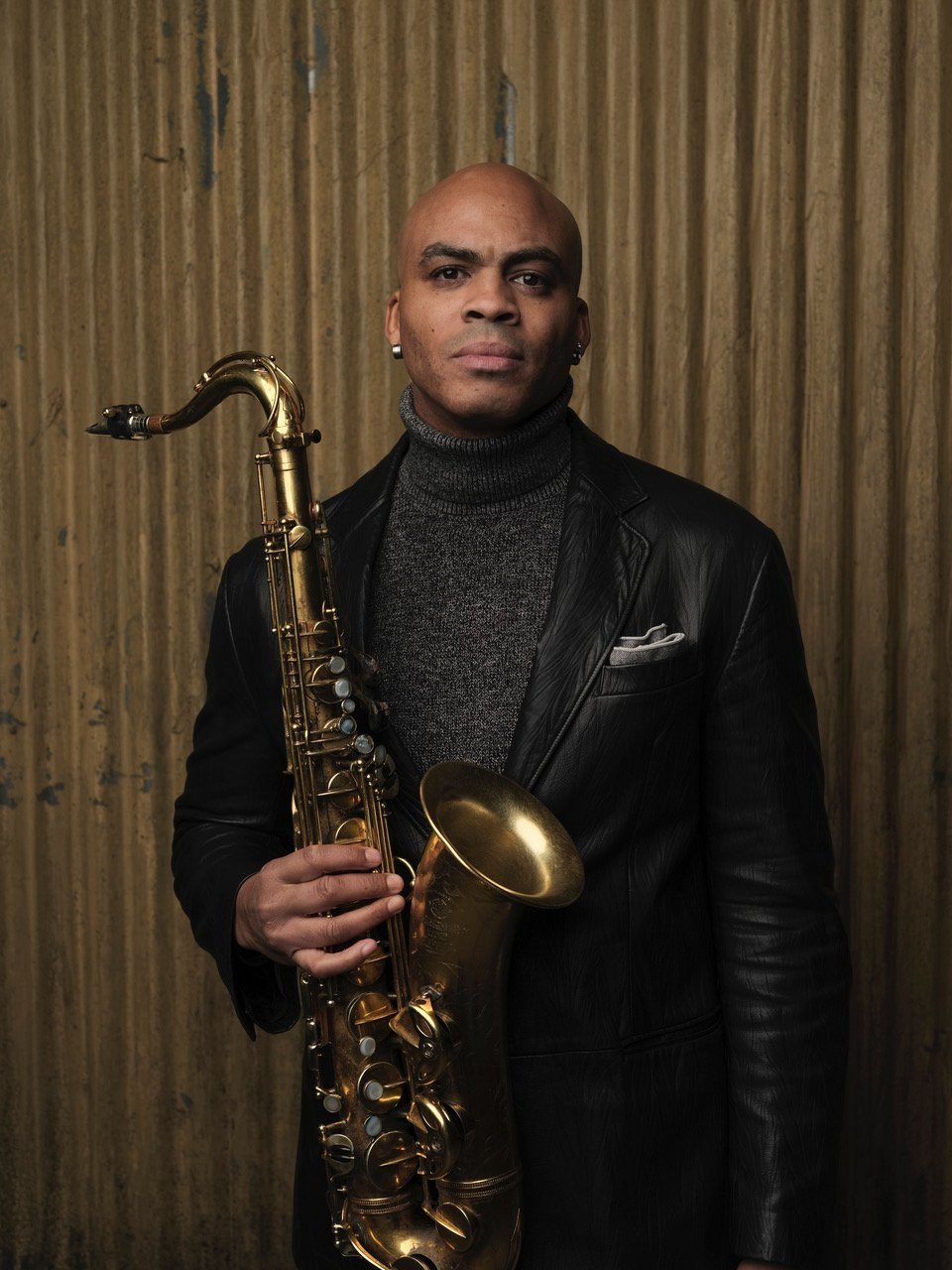

Among the musicians who performed Epitaph in 2007 was Grammy Award winning saxophonist, YSM Lecturer in Jazz, and Director of Yale Jazz Ensembles Wayne Escoffery.

Epitaph "served as an example of third-stream music, which was a term coined by Gunther Schuller in 1957—the idea of combining the concepts of jazz with the concepts of classical music," Escoffery said. "So that was in some ways its first significance, musically speaking. Epitaph represents a culmination of all of (Mingus') work. Mingus had a lot of influences and drew from a lot of places to make music." Escoffery also talked about the piece's cultural significance.

"It's not lost on me that this is the first time that Epitaph is being conducted by a conductor of color—myself and Ku-umba Frank Lacy," Escoffery said. "So that's a good and significant thing about this presentation of Epitaph. ... It's important, I think, for the listeners to know how studied and gifted Charles Mingus was as a composer, how important music was to him, and to understand that with Mingus, and especially musicians of that era, music was intertwined with their social reality. And their music was their vehicle for expressing how they were feeling and their tool in combating racism and dealing with equity."

Escoffery, along with trombonist Ku-umba Frank Lacy, will conduct the Mingus Big Band and students from Yale College and the Yale School of Music in the April 2 performance, which will take place less than a year since what would have been Mingus’ 100th birthday and a little more than a half-century after Mingus and dozens of jazz greats received Yale’s Duke Ellington Medal during a historic event at Yale.

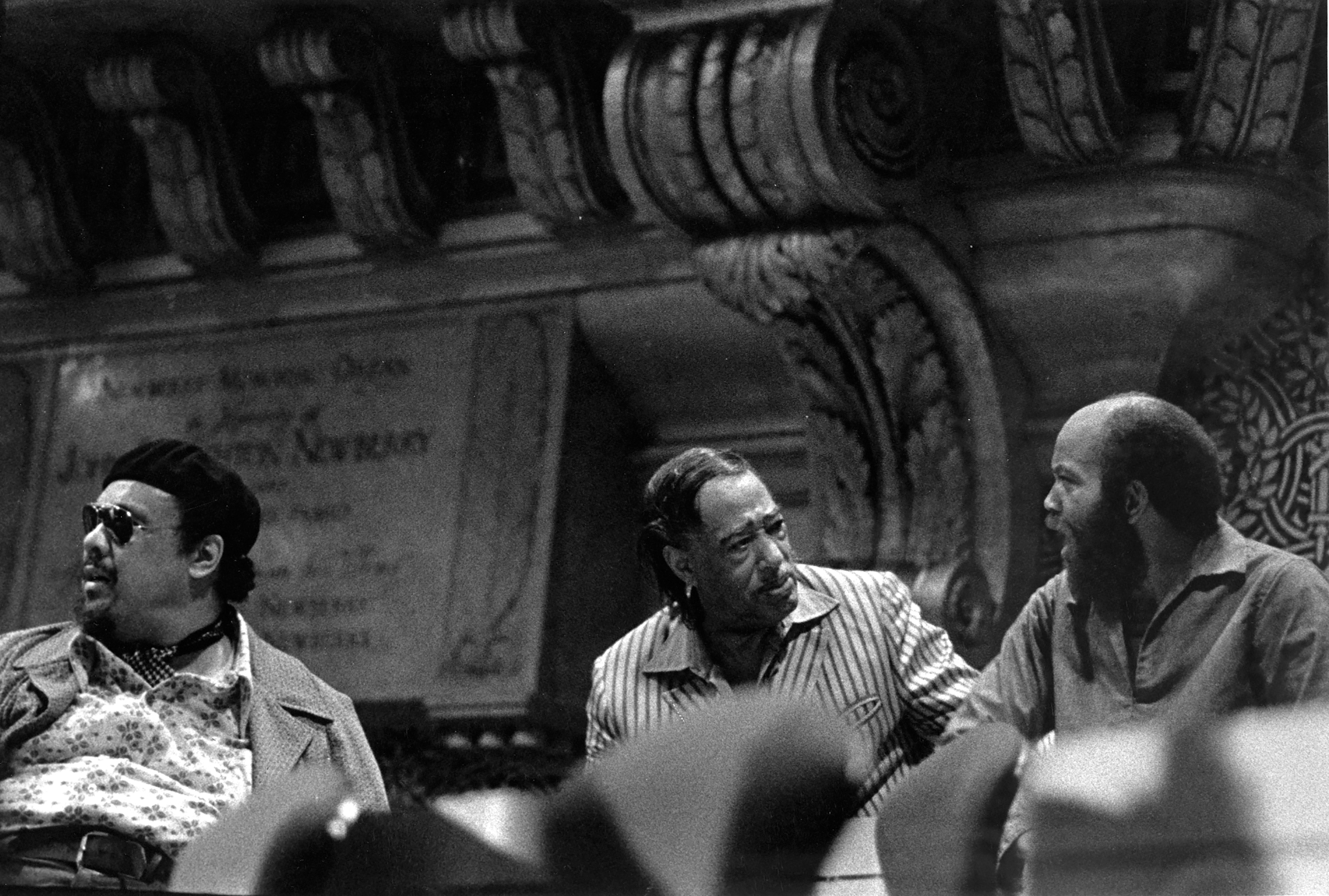

In October 1972, Prof. Willie Ruff ’53BM ’54MM brought dozens of jazz giants to Woolsey Hall for a historic jazz convocation—the “conservatory without walls,” as Ruff described it, through which Black music is introduced and passed on to new generations. Among the musical luminaries whom Ruff (now Prof. Emeritus of Music) welcomed to Yale were Ellington, Marian Anderson, and Mingus. It was the 1972 event at Woolsey Hall that established the Duke Ellington Fellowship at Yale and YSM’s Ellington Jazz Series—but not before a bomb threat during the convocation itself cleared Woolsey Hall of everyone but Mingus, who refused to bow to “a racist act” and remained onstage, playing Ruff’s bass, as the Yale Alumni Magazine recently recounted.

"The magnitude of the Mingus event is uniquely parallel" to that of the convocation in 1972, Duffy said, connecting the two programs and "the pioneering artists and music celebrated through each presentation."

While Mingus assumed he would never hear Epitaph performed in full—he famously said, “I wrote it for my tombstone”—the sonic yield of all 500 pages and 4,000 bars of his score will no doubt capture anew the imaginations of concertgoers who experience, over the course of two hours, Mingus’ undeniable musical genius.

The Ellington Jazz Series presents Epitaph: 100 Years of Mingus on Sunday, April 2, at 2 p.m., in Woolsey Hall. Learn more here.