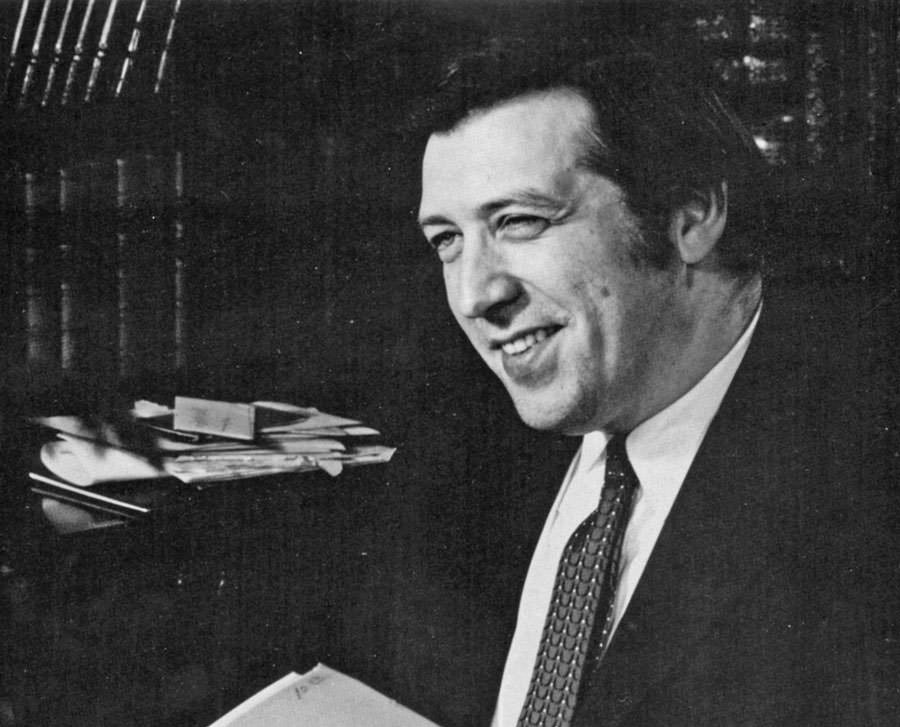

Gunther Schuller Dies at 89; taught at Yale in 1960s

Gunther Schuller, a composer, conductor, author and teacher who coined the term Third Stream to describe music that drew on the forms and resources of both classical and jazz, and who was its most important composer, died on Sunday in Boston. He was 89.

The cause was complications of leukemia, said his personal assistant, Jennique Horrigan.

Mr. Schuller, who won the Pulitzer Prize for his orchestral work “Of Reminiscences and Reflections” in 1994, was partial to the 12-tone methods of the Second Viennese School, but he was not inextricably bound to them. Always fascinated by jazz, he wrote arrangements as well as compositions for several jazz artists, most notably the Modern Jazz Quartet. Several of his scores — among them the Concertino (1958) for jazz quartet and orchestra, the “Seven Studies on Themes of Paul Klee” (1959) and an opera, “The Visitation” (1966) — used aspects of his Third Stream aesthetic, though usually with contemporary classical influences dominating.

Much of Mr. Schuller’s best music is scored for unusual instrumental combinations. In the Symphony for Brass and Percussion (1950), one of his most widely performed early works, he sent the strings and woodwinds to the sidelines. In “Spectra,” a study in orchestral color composed for the New York Philharmonic in 1960, he split the orchestra into seven distinct groups, deployed separately on the stage so that each could be heard independently or in combination with the others. He also composed “Five Pieces for Five Horns” (1952) and quartets for four double basses (1947) and four cellos (1958). His more than 20 concertos include showpieces for the double bass (1968), the contrabassoon (1978) and the alto saxophone (1983), as well as a Grand Concerto for Percussion and Keyboards (2005), for eight percussionists, a harpist and two keyboardists.

Some of his works were thorny and brash. But they could also be poetic and evocative. “Of Reminiscences and Reflections,” a rich, emotionally direct orchestral score, was composed as an elegy for Mr. Schuller’s wife, Marjorie, who died in November 1992. In his “Impromptus and Cadenzas” (1990), a chamber work, harmonic spikiness was offset by currents of lyricism and unpredictable shifts of mood and tone color.

As a composer, Mr. Schuller was self-taught. Although his career took him from the horn section of the Cincinnati Symphony and the pit of the Metropolitan Opera to a handful of influential positions — among them the presidency of the New England Conservatory and the artistic directorship of the Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood — he once described himself as “a high school dropout without a single earned degree.”

That he made this comment in a speech before the American Society of University Composers, in March 1980, was typical of Mr. Schuller. In addition to being fiercely proud of his self-taught status, he had an iconoclastic streak, and had a busy sideline delivering jeremiads in which he railed against either his listeners’ approach to music making or the musical world in general.

He told the university composers, for example, that it was time to abandon intellectual complexity for its own sake, and to write music that audiences could embrace — this despite his own devotion to the 12-tone method, which many listeners regarded as the root of the audience’s estrangement.

Only a few months earlier, in June 1979, Mr. Schuller had caused a stir by greeting the students who had come to Tanglewood to study at the Berkshire Music Center with an address in which he excoriated orchestras, orchestral musicians, conductors and unions for creating a situation in which, as he put it, “joy has gone out of the faces of many of our musicians,” replaced by “apathy, cynicism, hatred of new music” and other ills. Some of his arguments found their way into a compilation of his essays, “Musings: The Musical Worlds of Gunther Schuller” (1986), and his 1997 book, “The Compleat Conductor.”

But if Mr. Schuller learned composition on his own, he approached it with a solid grounding in musical basics. His paternal grandfather had been a conductor and teacher in Germany, and his father, Arthur Schuller, had played the violin in Germany under Wilhelm Furtwängler. Arthur Schuller joined the New York Philharmonic as a violinist and violist in 1923 and remained with the orchestra until 1965, and he encouraged his son to take up the flute and the French horn on the grounds that woodwind and brass players were in shorter supply than string players.

“I was fortunate to have been born into a musical home,” Mr. Schuller told The New York Times in 1977. “My father played with the New York Philharmonic for 42 years, and he had a lot of scores. When I was 11 or 12, I began buying my own scores, and at 13 I became a rabid record collector. Then, of course, there was playing. All of those things were my teachers, and they all complemented each other.”

[…]

Mr. Schuller’s teaching career began in 1950, when he joined the faculty of the Manhattan School of Music. He taught composition at Yale from 1964 to 1967, when he was appointed president of the New England Conservatory. During his decade in that position, he introduced jazz and Third Stream music as focuses of conservatory training.